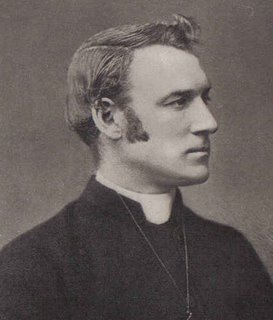

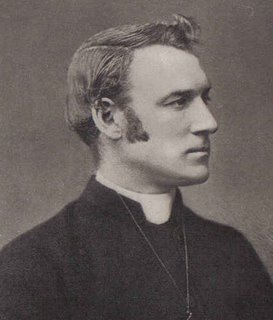

The attacks on the Church in Wales by Nonconformists like Henry Richard, alleging that the Church in Wales was no more than an Anglicising influence, alien to the spirit of the Welsh people, stung some in the Church in Wales into action. These men recognised that there was a spark of truth in the accusations. Most notable among these was Henry T. Edwards. Born in 1837, the third son of the Rev. William Edwards, Vicar of Llanymawddwy. Like his four brothers, H. T. Edwards entered the Ministry, being ordained deacon by Connop Thirlwall, Bishop of St. Davids in 1861, and received into full orders by Bishop John Vowler Short of St. Asaph in 1862 as Curate of Llangollen, assisting his father, who was by this time in poor health.

Ironically, Bishop Short was just the sort of Bishop H. T. Edwards would later attack. Formerly Bishop of Sodor and Man, and an evangelical, Short had been an interim appointment to the Diocese of St. Asaph under an abortive plan to amalgamate that diocese with neighbouring Bangor. He was not Welsh, he did not speak Welsh, and he did not like the Welsh, although he was an effective administrator.

Himself an energetic, bilingual preacher, whose ministry at Llangollen was blessed with conversions, and Henry Edwards' next concern, at a time when the Church in Wales was being attacked by Henry Richard for its poor provision of seatings, was the enlargement of the Parish church to accommodate the new converts. David Jones, his disciple and biographer, writes:

"In what he successfully did for the outward structure of his father's church at Llangollen, may be recognised his ideal conception of what should be universally effected in the Church of his fathers, not only in material, but also in intellectual and spiritual, reform."

In 1866, Edwards was appointed to the living of Aberdare in the South Wales Valleys. Aberdare, a centre of industry, was a very different place from Llangollen. With the aid of wealthy churchmen, Edwards set up a church extension society, to provide churches of the growing population of the region. When it came to Disestablishment, Edwards' policy could be summed up in the phrase 'reform and defence.'

In 1869, the same year in which he was appointed to Caernarvon, he wrote to Gladstone, then Prime Minister. His letter, later published as a pamphlet,

The Church of the Cymry. He began by conceding the numerical case:

"Now there are but few, I think, who, knowing Wales well, can venture to doubt that accurate statistics would show that seven-tenths of the native Cymric population of Wales are alienated from the Church of their forefathers. At the same time, the Church, as existing in Wales, inherits in a large measure the spiritual forces that have been found in all ages to exercise the most authoritative influence over the souls of men. She is strong in the undoubted inheritance of the spiritual authority of original mission to the ancient people who for more than two thousand years [...] have inhabited the valleys of Wales [...]."

In the view of Edwards, who was later appointed Dean of Bangor for his work, the Church had alienated the people, but not fatally. Appoint Welsh-speakers, attend to the work of teaching and evangelism, and the Church in Wales would not be ashamed. As for the claim made by the Liberation Society that Wales was 'A Nation of Nonconformists,' who would not accept the doctrine of the established church:

"Can it be said that the Nonconformity of the Cymric people is attributable to their unwillingness to accept the dogmatic teaching of the Church? It cannot. There prevails among the Nonconformist societies of Wales the utmost indifference, and, I may add, ignorance concerning systems of dogmatic teaching."

He believed that the Chapels were sincere but superficial in the presentation of Christianity and lacked the authority possessed by the Church in Wales, being regarded by the people as 'merely rival religious seminaries.' Once the Church in Wales reformed herself, she would be again the natural home of Welsh Christianity. Dissent, he explained, was due more to the practical than the doctrinal failings of the Church in Wales. Correct those, and the reasons for Dissent, and therefore Disestablishment, would vanish.

However historically correct he may have been, and there is no doubt that, from John Penry onwards, Welsh dissenters had left the Church because of her very real shortcomings, Edwards' programme was out of date. Besides, there were strong political pressures that would be brought to bear on the Church. Next time, we shall examine the scheme of Thomas Gee, Denbigh, for the Disestablishment of the Church.

I shall treat Dean Edwards in more depth at some other time. Suffice it to say, this little glimpse at a man who was called home before his three score and ten years were done has proved more interesting than I thought it would.

All quotations and the picture of Henry Edwards are taken from: David Jones (ed),

Wales and the Welsh Church: Papers by Henry T. Richards, MA, Late Dean of Bangor (London 1888). Additional information is from P.M.H Bell,

Disestablishment in Ireland and Wales, Roger L. Brown,

In Pursuit of a Welsh Episcopate (Wales, 2005).

Labels: Welsh Disestablishment