The History of a Historian - A.R. MacEwen. III

Labels: Alexander Robertson MacEwen

Turning the light of Celtic Reformed Church History on the Problems of the Modern Church

Labels: Alexander Robertson MacEwen

Labels: Alexander Robertson MacEwen

Labels: Preaching

Historians are usually thought of as people who write history rather than making it. This is really rather unfair, after all, Julius Caesar wrote history! Church historians are usually ministers, and all ministers have a life more or less interesting.

Historians are usually thought of as people who write history rather than making it. This is really rather unfair, after all, Julius Caesar wrote history! Church historians are usually ministers, and all ministers have a life more or less interesting.Labels: Alexander Robertson MacEwen

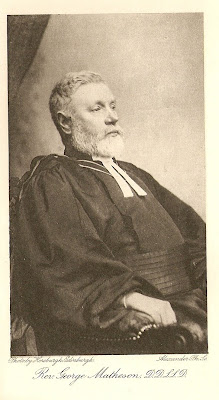

Labels: George Matheson

Labels: Events

Labels: Preaching

And the vicar found that people did come to the new church. But the ruins on the mountain, and Mary Roberts' gravestone, remain to speak of the old way of life.

More pictures of St. Peter's are here, on Tonyrefail.org, a reminder that the old church did not just serve Brynna, but many other settlements as well.

Labels: Churches

Labels: George Matheson

"I wrote a book," he said, "To show that evolution, if true, is quite compatible

with orthodoxy, but I have since come to the conclusion that evolution is not

true. I have no more fear of it than I ever had, but I am convinced that in,

say, twenty years it will be regarded as an exploded heresy. I am an unbeliver

in Drummondism.

Henry Drummond triumphantly waves his hand - you can almost see him do it - over

what he thinks is the strongest point in evolution, namely similar things

that in you and me are not of the slightest use, but in animals are of

great utility; his conclusion being, that we were animals forst and that these

things are survivals. My conclusion is not that at all; I would be driven to it

if no other explanation were reasonable. But if I want to make another staircase

in this house, there are two ways in which I can do it. I can begin afresh from

the ground floor or I can start at the first landing. I say that God Almighty

always adopts the latter method, to economise space and time; He makes the new

life start on the top of the old - not grow out of it; and that accords with the

whole analogy of nature. The first stair cannot itself get beyond the first

landing, but another stair may be built upon it. I believe in the eternity of

species [note that the term 'species' here does not mean exactly what modern

scientists mean, but has a broader meaning]; that all differences existed from

the beginning. I don't belive that first there was a trunk, and that this trunk

broke up into branches. I believe the branches were first."

"I am not in favour of it at all, for the simple reason that the novel with a

purpose always conveys to my mind the impression that it is a sermon from

the very outset., and the whole novel becomes a foregone conclusion. Now, I hold

that the sole aim of the novel should be to amuse, as it should be the sole aim

on the drama."

Labels: George Matheson

Labels: Churches

Labels: Preaching

The other chapel in Trebanog is the English Congregational Church. This is a slightly grander version of the Tin Tabernacle, with its round-headed windows and its semi-circular window over the door. It is taller than Mount Zion, and more ecclesiastical in appearance, although in the chapel, rather than the church style - no pointed windows here! Unlike Mount Zion, it still appears to have the original wall-cladding and windows.

Both of these old Tin Tabernacles are still in use and well-loved.

Labels: Churches