Preaching this Coming Lord's Day

Labels: Preaching

Turning the light of Celtic Reformed Church History on the Problems of the Modern Church

Labels: Preaching

Make me a captive, Lord, and then I shall be free.

Force me to render up my sword, and I shall conqueror be.

I sink in life’s alarms when by myself I stand;

Imprison me within Thine arms, and strong shall be my hand.

My heart is weak and poor until it master find;

It has no spring of action sure, it varies with the wind.

It cannot freely move till Thou has wrought its chain;

Enslave it with Thy matchless love, and deathless it shall reign.

My power is faint and low till I have learned to serve;

It lacks the needed fire to glow, it lacks the breeze to nerve.

It cannot drive the world until itself be driven;

Its flag can only be unfurled when Thou shalt breathe from heaven.

My will is not my own till Thou hast made it Thine;

If it would reach a monarch’s throne, it must its crown resign.

It only stands unbent amid the clashing strife,

When on Thy bosom it has leant, and found in Thee its life.God willing, we shall continue with Matheson next time.

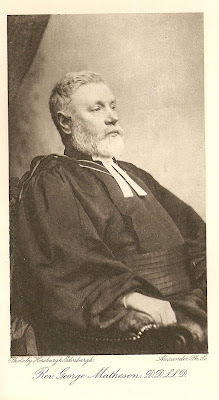

Labels: George Matheson

Labels: Preaching

Labels: George Matheson

"There must be some unusual attraction to bring people to such seats as these. We should never come but once, unless the pulpit had so much of intellectual and spiritual vitality as to make us forget where we were."

Yet these uncomfortable pews were crowded every Sunday! American visitors were amazed at the ability of the minister to 'read' the Bible from memory, but mot of all, it was his ability as a preacher, his ability to apprehend the life of the people. Pankhurst wrote: "Though his visual sight is entirely eclipsed he does 'see God', and he does see into the hearts of his hearers." What was the 'secret' of this? Simply put, blindness had made Matheson a man of prayer. His long struggles with pain and suffering had drawn him closer to God, and in his darkness he held communion with God. He held the most precious part of his work on the Lord's Day was to lead the congregation in prayer. "Prayer never causes me an effort," he said once. "When I pray I know I am addressing the Deity, but, when I preach, the devil may be among the congregation."

Yet his preaching was also precious to his hearers, as they heard Christ set forth. The power of his vivid imagination brought the Biblical narratives to life, and had the congregation hanging on his every word.

But he was a pastor, not just a preacher. Many would have forgiven the blind minister had he left the work of pastoral visitation to his elders, but no, Matheson, the great writer, the Royal preacher, the poet, insisted on visiting his own congregation - all 1500 members of the church, and many congregants who were not members. In addition to systematic pastoral visitation, he visited the sick, always with a word for Christ. And in addition to this, with the help of his secretary, he kept up with the literature of the day, while writing books and magazine articles! The congregation truly appreciated this pastoral care, all the more so as their pastor's own infirmities might have been used as a reason to excuse him from such work. The parish, in Stockbridge, had areas of deep deprivation, but Matheson gladly visited the poor and needy. This was a work few men in full health would have performed, and by his hard toil in this work, the blind minise on the hearts of his people. In six months he visited the whole membership, and confirmed that he was to be pastor, not just a preacher.

God willing, next time we shall continue with Matheson's adjustments to the pastorate at St. Bernard's.

Labels: George Matheson

Labels: George Matheson

In October 1885, George Matheson received one of the highest honours that a Church of Scotland minister could receive, he was invite to peak at Crathie Kirk (pictured) before Queen Victoria. Crathie is the parish Church for Balmoral, the Highland estate of the monarch of Scotland. It was a favourite residence of Queen Victoria, as it was connected with her beloved Prince Albert. Queen Victoria invited the more noted Church of Scotland clergy to take services at Crathie during her residence there. Victoria took her Christianity seriously, especially after the death of her husband. She had been given copies of Matheson's books of meditations by the Bishop of Ripon, and it was reading these that led to her invitation of the author to preach at her parish Church.

Matheson preached from James 5.2 on 'The Patience of Job'. The theme was Job's patient endurance of repeated and overwhelming calamities and submission to God through faith. He pointed out that Job never asked 'why?', even though his friends came forth with all manner of false explanations. They tried to trace the ways of God's providence, and they blundered terribly. Not so Job, he waited for God. And in all this Job pointed forward to the object of faith, Jesus of Nazareth, who suffered more than Job, and who is our hope and our redeemer. Here was comfort for suffering Christians. Queen Victoria greatly appreciated it and requested that the sermon be printed. The sermon was distributed among the Royal family, and Matheson had the chance to speak to many members of the Royal family. The blind preacher whose sisters had learned Greek and Latin to help him to learn had become one of the most important men in his denomination - and he remained incredibly humble.

His time at Innellan was coming to an end. In 1886 he was called to the pastorate of St. Bernard's Church, Edinburgh. God willing, next time we shall deal with the call to Edinburgh.

Labels: George Matheson

Labels: George Matheson

Labels: Announcements

Labels: George Matheson

'Patmos'

There is a spot beside the sea

Where I often long to go,

For there my God first met with me

When the sands of life were low.

I have had since more joy than pain,

And I've basked in fortune's smile;

But I never ceased to love the rain

That fell in Patmos' Isle.

It was indeed a tearful time

For my sun had set too soon;

The winter fell upon my prime

And the snows were thick in June;

And I thought my Father's face to be

Remote by many a mile,

In a place where there was no more sea

Unlike to Patmos Isle.

But in the deepest winter night

In the darkest nightly hour,

There came a gleam of golden light

Unknown to the summer flower.

The paths of God that brighter days

Had not stayed to reconcile

Were blended fast in rainbow blaze

Above lone Patmos isle.

I saw the clouds that earth reveals

Made chariots of the King;

The vials of wrath and judgement seals

Were the shadows of love's wing;

And when I knew by clouds he came,

I was glad to rest awhile

In the dark wherein was wrapt the flame

Of glorious Patmos isle.

And now the very dust of life

To my soul becomes most dear,

For by the path of human strife

Is His way emerging clear;

And when I see His track effaced,

Still my heart shall not resile,

Since the milestones of His march are traced

Through struggling Patmos Isle.

Labels: George Matheson

"If God can effectively communicate and act savingly through the imperfect human beings who are called to preach his gospel, why is it necessary to argue that the authors of Scripture were supernaturally kept from even the slightest discrepancy? In other words we must not tell God what the Bible ought to be like, based on our views of what God could and could not do." (p. 118-9)obscuring the issue by referring to preaching as if it were in the same category as the Spiration of the Bible (something that only really makes sense from James Orr's inherited perspective of an inspiration of persons rather than writings), in fact his position is that the originals of the Scriptures are NOT inerrant.

"My argument is that Scripture, having been divinely spirated, is as God intended it to be. Having freely chosen to use human beings, God knew what he was doing. He did not give us an inerrant autographical text, because he did not intend to do so. He gave us a text that reflects the humanity of its authors but that, at the same time, clearly evidences its origin in the divine speaking. Through the instrumentality of the Holy Spirit, God is perfectly able to use these Scriptures to accomplish his purposes." (p. 124).Now, if it is presumptuous and rationalistic for the inerrantists to say that God must have produced an inerrant text, is it not presumptuous for McGowan to say that God has not produced one? He cannot have it both ways, either he must be consistently agnostic about the question of inerrancy, or he must abandon the charge of presumption.

Labels: Books