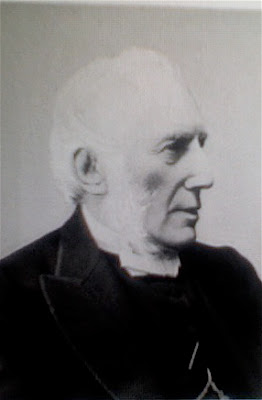

'This One Thing I Do.' John Brown of Broughton Place. - IX

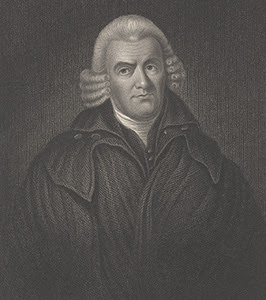

Although his grandfather was a famous author, and his own father had written extensively in vindication of the doctrines of free grace taught in the little book 'The Marrow of Modern Divinity' (really of Puritan Divinity), John Brown was practically forced into authorship. Whilst his father had been called to defend the doctrines of the denomination, John Brown was called upon to defend the central doctrine of Christianity - the deity of Christ.

Brown found himself forced into action by the Unitarian controversy that broke in Scotland in 1814. James Yates, minister of the Glasgow Unitarian congregation (chapel pictured). Yates was a strong believer in the Socinian dogmas of the supremacy of reason and the mere humanity of Christ, and he proclaimed them with zeal, calling forth from Ralph Wardlaw, congregational minister in Glasgow, a volume of Discourses on the Unitarian Controversy. Yates at once replied with A Vindication of Unitarianism. And there John Brown entered the controversy. He was asked by Dr. Andrew Thompson, editor of the Edinburgh Christian Instructor to write a review of Yates' book. But during the writing process the review swelled to such a size that Thompson advised it would be better published in a separate form, and this was done in April 1815 under the title Strictures on Mr. Yates' Vindication of Unitarianism, with a dedication to Doctor Lawson of Selkirk. The book sold well, but as the controversy faded, so did sales, Unitarianism, at least in the form Yates had proclaimed, was shown to be false, and lost its appeal. The book was a scathing reply to Yates' errors, and Yates retired from the field defeated. But John Brown was fairly launched as an author. So does God use the passing controversies of the day to raise up champions of truth.

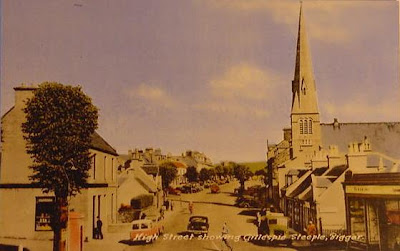

In the beginning of 1816 Brown found himself called to greater literary responsibility, as his denomination was launching a magazine. He was appointed editor, and for five years the pastor of Biggar was the busy editor of a theological journal. He managed to get the best theological minds of the denomination to write for the little magazine, including Doctor Lawson himself. The magazine never obtained a wide circulation, being regarded as a ministers' magazine rather than a magazine for the people in the pew. Still, it brought his name before people who had never heard of Biggar.

His second book was of a more lasting character than the first. Discourses suited to the Administration of the Lord's Supper was a volume of Communion sermons, discussing the doctrine of the Lord's Supper. Published in 1816, we are glad to say that it is back in print and can be found here.

It seemed that the young pastor of Biggar was marked for success. And it was then that the terrible blow fell, of which more next time.

Labels: John Brown Broughton Place