J. R. Jones, Ramoth lived in the county of Merioneth in North-West Wales. At the age of eighteen, he began to preach among the Independents (Congregationalists). However a Baptist mission to his home village of Llanuwchllyn led to his conversion to Baptist principles. He was ordained in 1788 to the ministry at Ramoth and was given oversight of the Baptist Churches throughout Merionethshire. Three years later, Christmas Evans took charge of the Chapel at Llangefni, with oversight of the Baptists of Anglesey.[1]

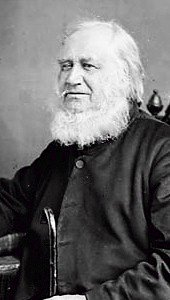

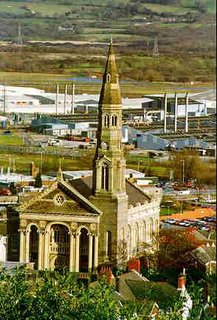

Born at Llandysul, Ceredigion on Christmas Day, 1766, Evans had experienced grinding poverty as a child. His father had died while Christmas Evans was an infant and he had been brought up by a drunkard uncle who had shamefully neglected him. The kindness of the Arian Minister of Llwynrhydowen, David Davies, had led to the young man receiving an education. Strangely enough, under the ministry of this markedly unorthodox man, young Christmas fell under deep conviction of sin. He listened intently to each sermon and then preached them back to the farm animals under his care! [2] In the course of his struggles with indwelling sin, Evans had to fight with men as well as the devil. While considering the call to preach, he was set on by a gang of ruffians who beat him to within an inch of his life, destroying his right eye. This, together with a vision of Christ’s Second Advent, Evans interpreted as a sign that he should continue to study for the ministry. After a period of supplying pulpits for the Methodists and Independents, he embraced Baptist principles and was baptised in the river Duar in 1788.[3] The denomination then stood on the cusp of a period of awakening. In 1789, the Baptists of North Wales invited Christmas Evans to conduct a mission among them. After a period of wrestling with God in prayer, Evans agreed. After two years in Lleyn, Caernarfonshire, he moved to Anglesey and took the pastorate of Llangefni, left vacant after the previous pastor had resigned in disgrace.[4]

In 1796, J. R. Jones, Ramoth, began to preach the principles of Sandemanianism among the Baptist Churches of North Wales:[5] Reading a number of the works of Alexander McLean, a leading Scottish Sandemanian, advocating ‘[…] a rigid observance of the Apostolical tenets and customs […]’, Jones became convinced in 1894 that this was true Christianity. Accordingly, he introduced such practices as the ‘Holy Kiss’ and foot washing to his church. The latter seems to have been met with serious opposition – and no wonder in an age where many of the common people went unshod![6] These practices were made mandatory in the churches that followed Jones, Ramoth. Hard on the heels of the practices of the Sandemanians came the doctrine. While bare belief of the truths contained in the Bible was seen as enough for saving faith, strict adherence to the peculiar practices was considered as necessary for soundness in the faith.[7] Sadly Christmas Evans, a man ‘[…] liable to be swayed to a great extent by the opinions of others’, was borne along in the Sandemanian tide.[8] He professed, in a letter of about 1796, addressed to a church in Swansea, as to faith: ‘This, wrought by the Lord, is no more than a belief in the word of the Lord as true; to believe the account of the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ […].’[9]

[1] J. Hugh Edwards, MP,

The Life of David Lloyd George with a Short History of the Welsh People (London, 1913), vol.ii, p.58.

[2] B. A. Ramsbottom,

Christmas Evans (Harpenden, 1985), pp.9-12. Indeed, the young farm-boy had created a ‘chapel’ for his ‘congregation,’ complete with pulpit!

[3] Tim Shenton,

Christmas Evans: The Life and Times of the one-eyed Preacher of Wales (Darlington, 2001), pp.61-2.

[4] Owen Jones, ‘Christmas Evans’, in

some of the Great Preachers of Wales (London, 1885, republished Hanley, 1995), pp.154-8.

[5] Thomas Rees,

History of Protestant Nonconformity in Wales, from its Rise to the Present Time (London, 1861), p.412.

[6] J. Hugh Edwards, MP,

The Life of David Lloyd George with a Short History of the Welsh People (London, 1913), vol.ii, pp.58-9.

[7] B. A. Ramsbottom,

Christmas Evans (Harpenden, 1985), pp.50-1.

[8] Owen Jones, ‘Christmas Evans’, in

some of the Great Preachers of Wales (London, 1885, republished Hanley, 1995), p.159.

[9] Quoted in Tim Shenton,

Christmas Evans: The Life and Times of the one-eyed Preacher of Wales (Darlington, 2001), p.171.

Labels: Christmas Evans and Sandemanianism