Welsh Nonconformity and Popular Culture 3: The Eisteddfod (Part One)

When it came to the churches reaching out into the world, sallying forth to capture the citadels of culture for Christ, there was an initial reluctance, born of persecution. In the days of discriminatory Acts of Parliament, it had been enough to thank God for the freedom to meet Equally, there was a common feeling that the world, opposed as it was to the Saints, had to be brought within the Chapel to be conquered, that if the Chapel went forth to capture the world it might itself be captured. Howell Harris and Daniel Rowland had opposed the performance of ‘Interludes,’ short pieces of drama (normally performed in churchyards), as the work of the Devil; while Williams Pantycelyn’s great poetic gifts had been employed as writer of popular devotional literature and hymns.

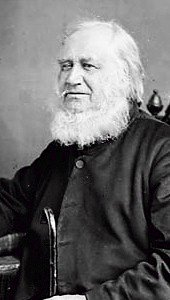

When it came to the churches reaching out into the world, sallying forth to capture the citadels of culture for Christ, there was an initial reluctance, born of persecution. In the days of discriminatory Acts of Parliament, it had been enough to thank God for the freedom to meet Equally, there was a common feeling that the world, opposed as it was to the Saints, had to be brought within the Chapel to be conquered, that if the Chapel went forth to capture the world it might itself be captured. Howell Harris and Daniel Rowland had opposed the performance of ‘Interludes,’ short pieces of drama (normally performed in churchyards), as the work of the Devil; while Williams Pantycelyn’s great poetic gifts had been employed as writer of popular devotional literature and hymns.Yet by 1840, things had begun to change, the traditional Nonconformist hostility to secular poetry being gradually challenged by a few men within Nonconformity. The first of these brave souls was William Williams of Denbigh (Caledfryn), who broke the mould by competing in the Wrexham Eisteddfod of 1820, and action he repeated a year later in Caernarfon. He was to be joined by two more natives of Denbigh, William Rees (Gwilyn Hiraethog-pictured), the winner of the first prize at the 1826 Brecon Eisteddfod, and Thomas Pierce, who competed in Eisteddfodau from 1839.[1] These men proved to be pioneers, leading a great flood into the Eisteddfodau from Chapels of all denominations. Although the Independents led the way, the Calvinistic Methodists and the Baptists were not slow to follow, many Chapels displaying the Bardic Chairs won by their ministers and members. The Baptist Chapels in Aberystwyth displaying three between them.[2]

Why did competing in the Eisteddfod prove so popular to Ministers? R. Tudur Jones suggested an answer in his Congregationalism in Wales, for Ministers, he averred:

"[The eisteddfod was] so clearly congenial to the spirit of an age which more

than anything else exalted competition and emphasized personal fulfillment and

satisfaction. Alongside this, there were also social reasons for the success of

the eisteddfod. Through it, a host of men who had not been to college and were

lacking in status had a suitable stage. They could adopt poetic and unusual

pseudonyms; to have a poetic pseudonym became in itself a sign of status.

Through becoming an eisteddfodic judge the literary man inherited authority in a

field of eminence as far as the social aspirations of the period were concerned.

He could reward the successful with literary immortality and consign the

unsuccessful to oblivion. In the Gorsedd of Bards, Nonconformist ministers could

enjoy ceremonial without becoming Anglicans, and the Gorsedd gave them an

opportunity to attain precedence over each other without denying their authority

as ministers.[3]"

[1] Jones, Congregationalism, p.177.

[2] Attendance at both chapels.

[3] Jones, Congregationalism, p.178.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home