Dr. John Alexander of Norwich: VI.

Since John Alexander was an unmarried man, the provision of a chapel was the first priority for the seceders from the Tabernacle. Regrettably the only pictures we have of the Tabernacle come from the end of its life, when it was badly maintained, and soon to be pulled down. They give no impression of its solid beauty. Designed by one of the greatest architects ever to work in Norwich in the 18th century, it was the sort of chapel no congregation would want to leave. But leave they had to.

The chapel in Princes Street (pictured) was nothing out of the ordinary. Some of the rooms behind the building, used as vestries and school rooms, were retained from the buildings that had previously occupied the site.

The chapel was described by a local paper as "a plain, heavy-looking structure, destitute of architectural pretensions." The 'gothick' glazing in the windows seem to give the lie to that. Pretensions there were, just modest ones.

Capacity was one of the first concerns. The building seated 1'000, with galleries around three sides. It cost £4,838 8/8, including the site and the cost of demolition. That did not of course include John Alexander's salary. The congregation, although large, was not wealthy, and at the time all of them would have to have paid a tax to support the Church of England as well as supporting their own church (the Church Rate was abolished in 1868).

Buildingproceededd quickly, and by the end of November the new chapel in Princes Street was ready (it was later discovered that one of the reasons for this swift construction was that corners had been cut, and less than ten years later the chapel needed repairs. In 1868 the building was completely reconstructed).

The last service in the Lancastrian School was held on November 28th, 1819, and on December 1st, the following Wednesday, the chapel was officially opened by Rev. Dr. Raffles from Liverpool (no relation to the amateur cracksman). Thus 'PrincesStreett' became synonymous with the chapel and its people.

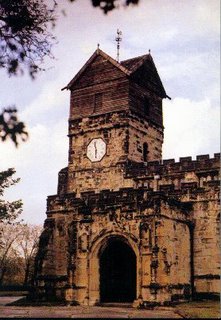

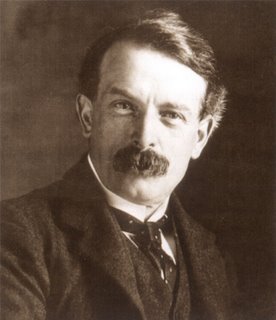

A church was formally constituted soon afterwards, and the first meeting of that congregational church was held on March 18th 1820, chaired by the Rev. W. Hull, pastor of the Old Meeting House Congregational Church, the oldest dissenting church in Norwich and the Rev. Alexander Creak of Great Yarmouth. Mr. Alexander wasreceivedd into membership from Bethesda Congregational Church, Liverpool, then the new church partook of the Lord's Supper for the first time. At the next meeting the newly formed church called Mr Alexander as minister, and he was ordained on May31st 1820.

All was not perfect, of course. For one thing the church had been forced to borrow money to build their chapel, and now the debt on it was a major source of worry. Indeed, the situation became so bad that in February 1825 Alexander wrote a letter of resignation and sent it to the church. It was never opened. The deacons, working tirelessly, managed to come to an agreement with the creditors to liquidate the debt of about £900 within five years. The cloud was lifted.

But all was not well. Another trial was about to strike. What it was we shall see, God willing, next time.

Labels: John Alexander